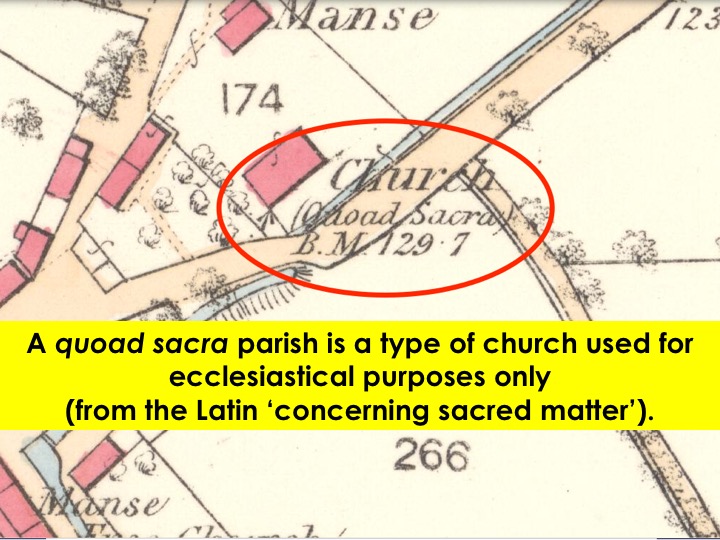

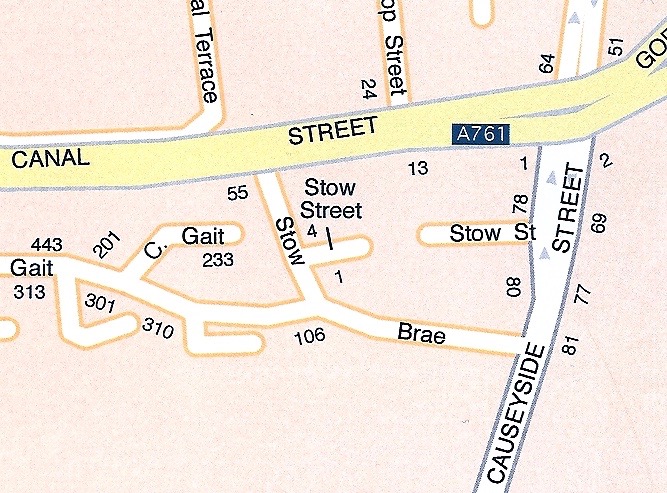

Contrary to common understanding, Stow’s family in Paisley was not especially wealthy. Granted William, the head of the family of ten children, owned three houses, plus the feu duties in Stow Street and Stow Place, but the 1825 codicil to his will adjures ‘such of my children as are not settled in life nor have any establishment of their own, to live together in the most harmonious and cheapest way’. So anxious was he for their welfare that he was forced to apply to his brother in Berwick-upon-Tweed[footnote]Stow’s favourite Uncle David, Rear Admiral.[/footnote]

to make provision for the unmarried daughters (Elizabeth, Margaret and Marjorie). The £600 each of these received appears to have been badly invested for by 1829, another codicil was added to the will: ‘There is, owing to bad trade, a great depreciation of heritable property and as I have lent out money upon bond upon tradesmen’s houses and placed it in the name of my unmarried Daughters and as it is probably that they may lose by it I therefore by this Codicil ordain that the property shall be valued by Judges, and that they are to have that property according to their division that all be alike.

It is not unreasonable to suppose, therefore, that in 1811, at the age of eighteen, David as the second son had no choice but to move to Glasgow where he was indeed ‘a clerk in a counting house’ as Fraser states. The counting house was ‘Wilson, Hervey and Co. Silk warehouse’, No. 115 on the south side of the Trongate, so named because of the large weighing and measuring scales for merchants at the market cross. Even in Stow’s day the area was associated with commerce and innovation.[footnote]In 1818 James Hamilton, who owned a grocer’s shop at 128 Trongate was the first to introduce gas lighting and in 1821 the dials of the steeple of St Mary’s Parish Church (the ‘Tron Church’ were illuminated by gas reflectors, the first attempt in the UK. (Foreman, Carol. (2007) Glasgow street names. Edinburgh, Birlinn).[/footnote]The first street lights were provided on the south side in 1780, to reward the shopkeepers for constructing a pavement [footnote]Foreman, Carol. Glasgow street names. Edinburgh, Birlinn, 2007, p. 157.[/footnote]and the ‘plainstanes’ or pavement in front of the Tontine coffee house nearby had once echoed to the sound of the barter of the ‘tobacco lords’.

The ‘Wilson’ was Stow’s brother-in-law, John, who had married his eldest sister, Ann, in 1807. The Herveys were close friends. John Hervey’s daughter was married to (unhelpfully) another John Wilson who was also a silk merchant: Rev Patrick Mcfarlan, a staunch supporter of the Glasgow Infant School Society, officiated at the wedding. The business was still listed as ‘Wilson, Hervey and Co. as late as 1816 [footnote]Foreman, Carol. Glasgow street names. Edinburgh, Birlinn, 2007, p. 157.[/footnote]but in 1817 it was entered as ‘Wilson, Stow and Co, Silk Warehouse’. In that year Stow became a burgess of the city of Glasgow.

‘Stow, David, merchant, one of the partners of Wilson, Stow and Company, silk merchants, 115, Trongate, (admitted Burgess and Guild Brother by purchase – August 11th, 1817’. [footnote]Scottish Record Society: the Burgesses and Guild Brethren of Glasgow 1751-1846, Vol. 2 Edinburgh 1935 p. 309.[/footnote] Stow was launched on his mercantile career.

By 1825 the ‘silk warehouse’ was at 38, Argyle Street, moving to 76, Argyle Street in 1826. In 1832, John Wilson died, leaving Stow in sole charge of the Company. By 1834-5, the business had moved to even more salubrious surroundings at 85, Buchanan Street. Buchanan Street had been originally considered too far west to be a viable property, but from the late eighteenth century the first residences began to be built. It was not until the opening of the Argyll Arcade in 1828 that commercial premises began to appear. Stow obviously moved in the wake of that venture.[footnote]O.S. Map 1857-58, NLS; photograph from Foreman, Carole. (2007) op cit.[/footnote]

Sometime before 1825, a new branch of the business was established at Guildford Street, Leeds.[footnote]‘Conveyance of a share of the partnership in premises in Leeds from David Stow of Glasgow to William Fenwick Stow of Leeds and Matthew Stow of Leeds (1852)’ (Leeds Archives) and Glasgow Post Office Directories 1815-1836.[/footnote] This enterprise initially involved John Wilson and the two Stow brothers, David and William Fenwick, who purchased a plot with others for £1,554.17.6 to build a warehouse. Since ‘the said John Wilson David Stow and William Fenwick Stow had made the said purchase by and out of the monies of the Partnership Trade and Business carried on by them in Leeds’ Stow must have been trading in Leeds before 1825. In 1833, after John Wilson’s death, his partnership was initially inherited by Ann, his widow, and then Lorraine his eldest son:

The said John Wilson departed this life on or about the twentieth day of August One thousand, eight hundred and thirty two intestate and Letters of administration of his goods, Chattels, rights and credits were shortly afterwards duly granted to Ann Stow Wilson his widow by and out of the Exchequer Court of the Archbishop of York And whereas by Indenture bearing date on or about the seventeenth day of December One thousand, eight hundred and thirty three and made between the said Ann Stow Wilson of the first part and Lorraine Wilson therein described as the eldest son and heir at law of the said John Wilson.

However, Stow and his brother bought out this share for £1,254.3.4. In 1840, they mortgaged their share to the other partners for £3,820 and some time after 1845 [footnote]Interestingly, the date is left blank in the Conveyance.[/footnote] Matthew Kenyon- Stow, Stow’s youngest brother, joined the firm which was by now ‘Stow, brothers and Company’. By 1852, Stow having paid off his share of the mortgage, was bought out for 5 shillings. The Glasgow Post Office address is given as ‘Guildford Street’ just off the famous ‘Heads Row’ in Leeds. Land ‘Fountain Street’ was also purchased.

The Leeds Branch may have been re-mortgaged to finance the purchase of ‘The Port Eglinton Spinning Company’, in 1847-8. This was a shrewd business move since Port Eglinton benefited from being on the Paisley-Glasgow canal [footnote]Which, ran close to Stow Street, Paisley, where Stow’s family lived.[/footnote] a half-hourly bus service for workers (although many lived nearby), and the railway. The Port Eglinton Spinning Company was a very substantial Mill:

‘The building forms almost a square, having Eglinton Street on the east, Francis Street on the west, Victoria Street to the south, and Canal Street on the North. The frontage to Eglinton Street is five storeys in height, and extends in length nearly 250 feet. Immediately behind the front building is a court, some fifteen or twenty feet in width, which separates it from a three-storey erection of brick, used for preparing wool in the rough. Then comes another court of similar width, which is bounded on the west by a third building, extending from Victoria Street to Canal Street.’ [footnote]The Scotsman, 23rd of January, 1874.[/footnote]

Port Eglinton was a busy site with an iron foundry, several other factories. The following accident might well have involved one of Stow’s employees:

About ten o’clock on Thursday forenoon, a number of boys got in about the goods station of the Glasgow and Ayr Railway Company, Port Eglinton, and commenced pushing along a line of rails one of the empty trucks. They had not been long thus employed, when one of their number, a boy aged about ten years, the son of a carpet weaver residing in Bedford Street, fell before the wheels of the carriage, which passed over his body. The boy was immediately conveyed home, and medical aid procured, but we regret to add he expired in about an hour afterwards. [footnote]The Scotsman, Saturday 2nd November 1844[/footnote]

Stow also made legal history. In 1842 in ‘Inglis v. Port Eglinton Spinning Company’ it was laid down that an insolvent could reject goods sent to him after he became bankrupt, but could not then use them to pay off creditors, or accept a portion of them later [footnote] Burton, John Hill. The Law of Bankruptcy, Insolvency, and Mercantile Sequestration in Scotland Edinburgh: William Tait, 1845 pps. 191, 2. [/footnote]

By 1852 John Freebairn and David George, two of Stow’s sons, appear in the firm, although John died in that year. David George, therefore became Stow’s sole male heir and he ensured that his will allowed David George to take over the reins immediately on his death:

Immediately after my decease to appropriate assign and transfer to my son David George Stow in fee to the Credit of his Account with the Port Eglinton Spinning Company out of the sum at my Credit with the said Company the sum of £3500. [footnote]GROS. Stow’s will[/footnote]

Thereafter, David George and Jessie Graham, his wife, inherited the company, which at Stow’s death was valued at £22,864. However, in 1874, ten years after Stow’s death, part of the Port Eglinton Spinning Company burned down.

‘About noon yesterday fire broke out in the Port Eglinton Spinning Mill, situated near the south the end of Eglinton Street, Glasgow, and before the flames were got under, damage to the extent of from £10,000-£12,000 was done.’

The fire originated in the reeling and finishing mill and because of the nature of the material spread rapidly. About 250 girls were forced to evacuate along with ‘A great number of families who inhabit houses in Francis Street, contiguous to the fire, were during the time this scene was being enacted busily engaged carrying their chattels to the street.

Despite the best efforts of the Fire Brigade the mill fronting Canal Street was soon ablaze. : ‘the iron girders shortly afterwards showed signs of giving way, and in a few minutes the whole front wall fell out into the street…….. One engine situated in the spinning and finishing mill, was destroyed, in addition to a large quantity of valuable machinery. [footnote]The Scotsman, 23rd of January, 1874.[/footnote]

The fire resulted in all the employees being thrown out of work, but the buildings were exceedingly well insured. Stow had been a Director of one of the first insurance companies, ‘The Scottish Provident Institution’ in Edinburgh and the Mill covered (with a number of other companies) for £55,000.

According to a document, probably dated 1898, found in Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, the Caledonian Central Station Co. demolished the remaining buildings. The Caledonian Railway Company was formed in 1845 and originally ran trains between Carlisle, Glasgow and Edinburgh. In 1848, the company ran the first direct train from Scotland to London. The engines used were painted a shade of blues that became known as “Caledonian Blue”. [footnote]SCRAN[/footnote]

By 1881, the English Census of that year indicates that David George Stow had moved, with his family, to 32, Princes Square, Paddington. He was only 51 and spent the rest of his years in the south of England, dying in 1865 in Rochford, Essex at the age of 65. Maybe he had inherited the family’s poor health: maybe the insurance money was too tempting.

As a postscript, Andrew Aird in his book ‘Glimpses of Old Glasgow’ refers to Cumberland Street in Hutchesontown where was the ‘Port Eglington Hotel and the entrance to the Paisley and Johnstone Canal. Immediately above this was the large wool-spinning and carpet manufacturer of Wilson, Stow and Co. the chief partner of which was the late Mr David Stow’. [footnote]Aird, Andrew. (1894) Glimpses of Old Glasgow, p108 Available at http://gdl.cdlr.strath.ac.uk/airgli/index.html. (8 April, 2010).[/footnote]

Throughout his life Stow describes himself variously as a: Manufacturer: Roll of the Freemen of Berwick 1800-1899;

Silk Merchant: Glasgow Burgesses and Guild Brethren 1811-1825

Silk mercer: Glasgow Post Office Directory 1828

Silk and Stuff (archaic name for worsted cloth): Glasgow Post Office Directory, 1829

Woollen Manufacturer: Scottish Census 1841

Mill Owner: Scottish Census 1861

Merchant: Sarah and Agnes Stow’s baptismal records; William’s entry in Glasgow University’s Academic Lists; his own Death Certificate; Inventory of his Estate;

Worsted and Spinner: Sarah Stow’s death certificate

Yet at his death more than half of Stow’s wealth was tied up in property and from the scraps of information available, he might be better described as a property developer.[footnote]1844 Sylvan Manuscripts: Reconveyance of land and houses in St. Pancras, Middlesex, between David Stow of Glasgow, merchant, William Henry Langley of John Street, Bedford Row, gent, Francis Parkyn of Bedford Street. A triangular piece of ground in St. Pancras of 1 acre, bounded by the Hampstead, Kentish Town Road, and Ferdinand Street, with all houses erected thereon. http://www.durtnall.org.uk/DEEDS/Middlesex%201102-1201.htm.[/footnote]

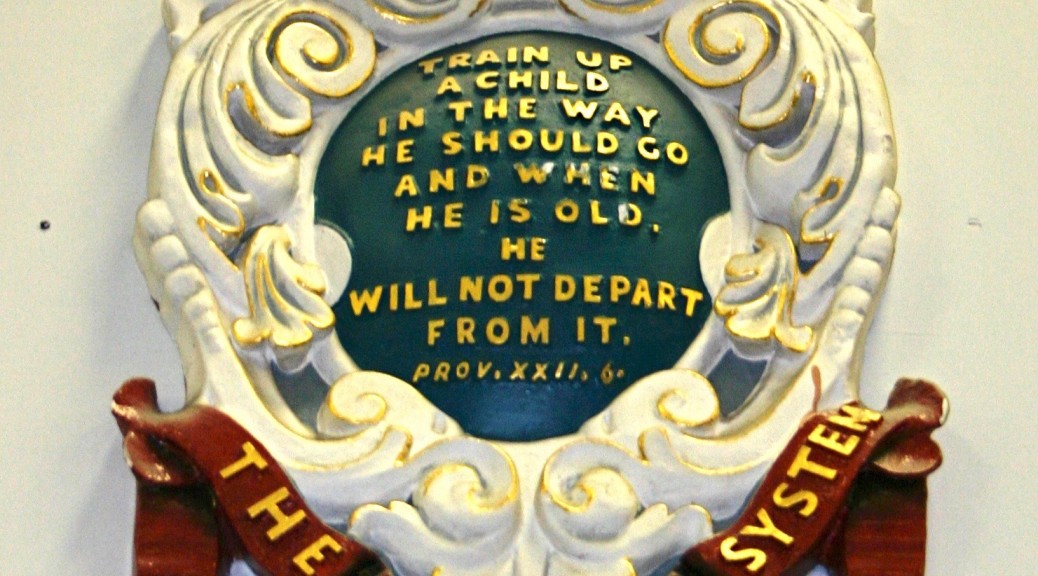

Stow does not seem to have been particularly interested in his business. In the early years he spent a great deal of his time on church work, being involved in the Parish Poor Relief and taking a very active part in establishing and maintaining the Sabbath Schools in St John’s. When the Normal Seminary was opened in 1837, and possibly before hand in the two model schools were open, he spent Tuesday and Thursday afternoons attending the public ‘criticism’ lessons. He never attained the huge financial sums such as his compatriots James McConnel and John Kennedy, from whom his father and possibly Stow bought machinery.[footnote]

1844 Sylvan Manuscripts: Reconveyance of land and houses in St. Pancras, Middlesex, between David Stow of Glasgow, merchant, William Henry Langley of John Street, Bedford Row, gent, Francis Parkyn of Bedford Street. A triangular piece of ground in St. Pancras of 1 acre, bounded by the Hampstead, Kentish Town Road, and Ferdinand Street, with all houses erected thereon.http://www.durtnall.org.uk/DEEDS/Middlesex%201102-1201.htm.[/footnote]

They had moved to Manchester and ‘set up their own firm in 1795 with an initial capital of £1,770…… by 1810 their capital had risen to £88,000………, By 1820 the company had three mills and had established itself as the leading spinner of fine cotton in Manchester,’[19][footnote] Fulcher, James. (2004) Capitalism: A very short introduction. Oxford, O.U.P. [/footnote] Conversely, Wood (1986) suggests that, in modern terms, Stow spent between £100,000 and £150,000 on his educational interests.[footnote] Wood, op cit. p. 74[/footnote]

Stow’s business affairs are crucial to his story. Had he concentrated on his carpets he would have been a wealthier man; but had he done so, there would be no story to tell.

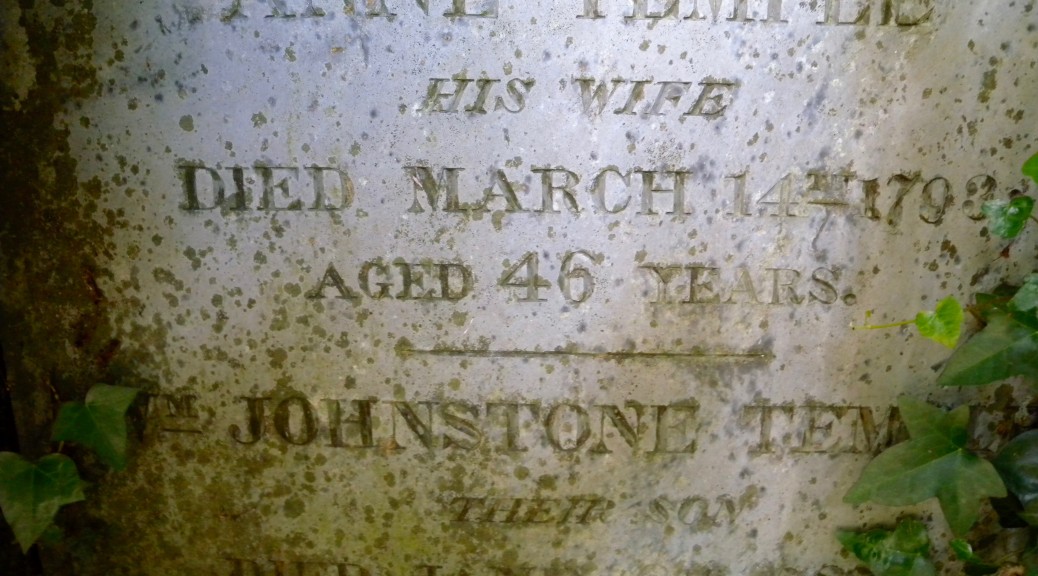

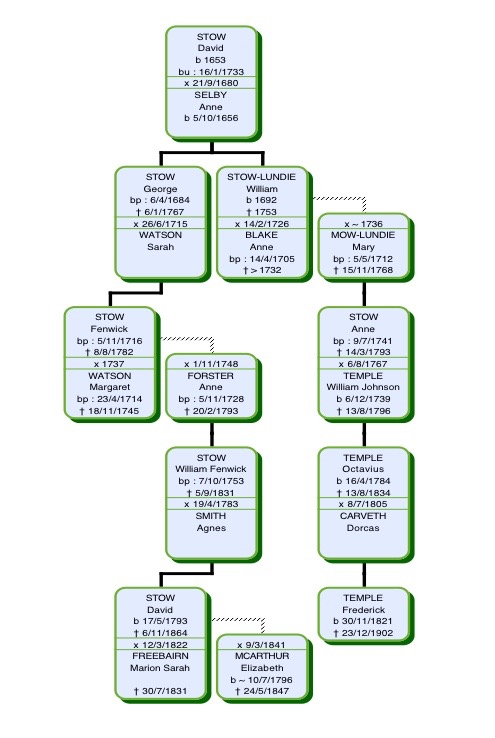

Frederick Temple (1821-1902) was Stow’s fourth cousin, his grandmother (Anne Stow) being a cousin of Stow’s grandfather (Fenwick Stow). There is no solid evidence that Stow and Temple ever met but ‘Frederick Temple claimed to belong to the Stowe branch of the Temple family, of which Richard Grenville, third duke of Buckingham and Chandos, was the head’[footnote]Spooner, H. M. ‘Temple, Frederick (1821–1902).’ Rev. Mark D. Chapman. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. Jan. 2008. 15 June 2009 <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/36451>.[/footnote] and it is inconceivable that Sir James Kay Shuttleworth, a mutual friend, did not introduce the two men. Following an education at Eton, Temple went on to Oxford leaving in 1848, ‘on the advice of Sir J. P. Kay Shuttleworth to undertake work under the committee of council on education, first as examiner in the education office at Whitehall until the end of 1849, then as principal of Kneller Hall, between Whitton and Twickenham, a training college for workhouse schoolmasters’.[footnote]Ibid.[/footnote]

Frederick Temple (1821-1902) was Stow’s fourth cousin, his grandmother (Anne Stow) being a cousin of Stow’s grandfather (Fenwick Stow). There is no solid evidence that Stow and Temple ever met but ‘Frederick Temple claimed to belong to the Stowe branch of the Temple family, of which Richard Grenville, third duke of Buckingham and Chandos, was the head’[footnote]Spooner, H. M. ‘Temple, Frederick (1821–1902).’ Rev. Mark D. Chapman. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison. Oxford: OUP, 2004. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. Jan. 2008. 15 June 2009 <http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/36451>.[/footnote] and it is inconceivable that Sir James Kay Shuttleworth, a mutual friend, did not introduce the two men. Following an education at Eton, Temple went on to Oxford leaving in 1848, ‘on the advice of Sir J. P. Kay Shuttleworth to undertake work under the committee of council on education, first as examiner in the education office at Whitehall until the end of 1849, then as principal of Kneller Hall, between Whitton and Twickenham, a training college for workhouse schoolmasters’.[footnote]Ibid.[/footnote]