‘I thocht maisters didna need to be taught. Gin ye had said sic a thing to my auld maister, he would hae crowned you wi’ his auld mooldy wig in a twinkling – that he would – and maybe gi’en ye a loofie (palmie) or twa to the bargain; – schoolmaisters to be taught! Ye’re no blait the day, I think. Maisters surely were no taught, langsyne, were they?’ [footnote](1860) Granny and Leezy 6th ed. London: Longman, Green, Longman and Robarts. p. 60, digitised version on this website[/footnote]

As public interest in infant schools – and the pupil exhibitions – waned, so enthusiasm for a debate about teaching methods, and particularly the usefulness of teacher-training, grew.

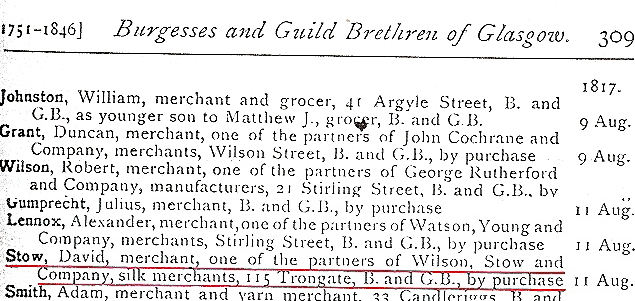

It was the Vice-President of the Glasgow Infant School Society, John Campbell Colquhoun of Killermont, who initiated the change of direction. At this time, teachers, for Stow, were but a necessary concomitant to the moral uplift of society through the education of children and sufficient numbers for his purpose were being produced through the existing model schools. By 1836, that is before the opening of the Normal Seminary, [footnote]See p. 2 of the digitised version of The Glasgow Educational Society’s Appeal Letter. The Appendix to Stow. (1860) Granny and Leezy, 6th ed. also calculates the numbers of teachers being trained in the model schools prior to the opening of the college in 1837.[/footnote]

Stow claimed that 260 teachers had been trained at the Model Infant and Juvenile Schools. Rusk notes [footnote]Rusk, Robert. The Training of Teachers in Scotland. Edinburgh: The Educational Institute of Scotland. 1928, p.62.[/footnote] that the early editions of his works are entitled ‘Moral Training’; the term ‘The Training System’ was only employed later when his focus had changed to the training of teachers. Nevertheless, he was soon caught up in the ‘friendly contests’[footnote]Stow’s expression, see Glasgow Educational Society Third Report 1836, p.7[/footnote]in the press and the debates and lectures which followed Colquhoun’s initiative and before long he was devoting his usual energies to the cause.

On 25th October, 1833, Colquhoun circulated a series of enquiries among the clergy and schoolmasters concerning the state of education in Scotland.[footnote] See correspondence in The Glasgow Herald, 10 February and 14 March 1834.[/footnote] This was probably prompted by a:

‘desire to respond to the call of the present Lord Chancellor of England,[footnote]John Charles Spencer, Viscount Althorp (1782–1845).[/footnote]

who at the recent Wilberforce meeting at York, is reported to have said, ‘that the efforts of the people were still wanting to promote education, and that Parliament would do nothing until they themselves took the matter in hand with energy and spirit, and with the determination to do something.’[footnote]From the third ‘Resolution’ taken at the first meeting of the Society on 24th February, 1834.[/footnote]

Not everyone agreed with the tenor of the enquiry which presupposed that parish schools were in a parlous state.[footnote]See the letter from the Parish Schoolmaster, Kirknewton, dated 25th January 1834 lauding the quality of both the parish system and its teachers. Cf. the response in the second ‘Resolution’ of the Society.[/footnote]

Despite this, Colquhoun called a meeting for the 24th, February, 1834 when the Glasgow Education Association (as it was then) was launched.[footnote]Despite Stow’s argument that the Glasgow Educational Society succeeded the Glasgow Infant School Society, this is not chronologically accurate. GISS was still holding an Annual General Meeting in 1834, and advertisements for lectures offered by both Societies appear in for 3rd November 1834.[/footnote]

The Association’s aims were formulated, and a committee,[footnote]The original group involved in the circular and questionnaire included, besides Colquhoun, Rev Dr David Welsh, Rev George Lewis, Rev R. Buchanan, Rev J. Lorimer, Rev. C. J. Brown, H. Dunlop and William Collins. Stow was initially a member of the committee, only later becoming Joint Secretary with George Lewis and then, on Lewis’s departure for Perth, sole Secretary.[/footnote] including Stow as a member, constituted. An advertisement to this effect was placed in the Glasgow Herald on April 11th, 1834 and this marks the official beginning of the Association. Colquhoun was appointed as the first President(11)

[footnote]A vice-president of the Glasgow Infant School Society which does suggest some continuity.[/footnote]

and on the 2nd October 1834, he chaired a meeting on the subject of ‘extending the Parochial Schools in Scotland’. It was addressed to the ‘Friends of Education and of our Religious Institutes in Glasgow’. Stow must have felt himself included on both counts. As the Secretary of the Infant School Society and joint founder of five infant schools in the previous six years, he could not but decry the paucity of educational provision in the city and any public meeting or society which aimed to improve the situation must have attracted his support. Similarly, he considered himself a practising member of the Evangelical wing of the Church of Scotland and an enthusiastic Sabbath School teacher. Without the benefits of hindsight, it must have seemed totally advantageous to Stow to attend meetings and join an Association whose avowed aim was to extend the parochial school system through the structure and organisation of the national church: ‘To the Church Evangelicals in particular, the necessary identification of national religion and national education was self-evident and the duties of government, any government, to promote both were just as obvious’.(12)

[footnote]

- Withrington Donald J. ‘Scotland a Half-Educated Nation’ in 1834 – A Reliable Critique or Persuasive Polemic?’ in Humes and Paterson, Scottish Culture and Scottish Education 1800 – 1980. Edinburgh: J. Donald, 1983, p. 58.

[/footnote]

That Stow, with Chalmers and twenty-three other members of the Committee,(13)

[footnote]A comparison of the Committee members of the Glasgow Educational Society with the Book of the Picture of the Disruption by David Octavius Hill, reveals that Blackie, Brown, Buchanan, Campbell, Chalmers, Collins, Dunlop, Forbes, Fraser, Gibson, Henderson, Heugh, Kidston, Lewis, Macdonald, McFarlane, Miller, Paterson, Rainy, Smyth, Somerville, Stevenson and Welsh joined the Free Church of Scotland with Stow. [/footnote]

would join the ranks of the Free Church within nine years, and thus lose all influence over the institutions he was about to found and finance must have seemed scarcely credible at the time.

It has been suggested that the odd numbering of the GES reports (3-5) indicates that the two published GISS reports (1-2) are to be regarded as part of the same sequence. Indeed, in a memoranda written for Kay-Shuttleworth in 1840, Stow states ‘The first and second reports (i.e. of GISS) were published in 1829 and 1830, and an interval of five years elapsed before the third report appeared’(14)

[footnote]

- i.e in 1835, after the Glasgow Infant School Society had closed.

[/footnote]

perhaps suggesting that Stow considered that the Reports of the two societies were numbered sequentially and were proof of a link. However, George Lewis’s essay ‘Scotland – a half-educated nation’ and the pamphlet ‘Hints towards the formation of a Normal Seminary in Glasgow for the professional training of schoolmasters’,(15)

[footnote]

- Hints towards the formation of a Normal Seminary in Glasgow for the professional training of schoolmasters, not dated but, from internal evidence, probably published 1835, later than originally thought.

[/footnote]

which are often regarded as a independent documents, were both published ‘Under the Superintendence of the Glasgow Educational Society’ and are numbered I and II respectively. It is more likely, therefore, that these are the first two GES Reports. In this case, despite the eventual overlap, it is at least arguable that the Glasgow Education Association was a distinct scheme for the training of teachers initiated by Colquhoun, as a Member of Parliament, with a political rather than pietistic impetus. Had the political initiative continued, teacher education in Scotland might have taken a significantly different route.(16)

[footnote]

- Colquhoun and Lewis were both for parochial provision by the Church of Scotland and against the Voluntaries call for state (that is non-church) provision and disestablishment. Neither might have introduced Stow’s brand of intense evangelicalism.

[/footnote]

By 15th May, 1835,(17)

[footnote]

- The Glasgow Herald, May 15th, 1835. Cf. the use of the new name in ‘Hints towards the formation of a Normal Seminary in Glasgow for the professional training of schoolmasters’.

[/footnote]

however, the name had changed to the Glasgow Educational Society, suggesting that the aims of the Glasgow Infant School Society had been absorbed into the new Society and with them the religious motivation. Despite the distinctive origins of two Societies, Stow was obviously keenly involved in the new venture. In the inaugural meeting of 2nd October, 1834, already noted, he made a hallmark speech that the Bible must be explained and not merely taught in school and that ‘a juvenile school (is) not simply for teaching or training the intellect alone but for training the whole man – physical, intellectual and moral’.(18)

[footnote]Quoted Withrington (1983) op cit, p. 65.[/footnote]

By 1836, when the third report(19)

[footnote]Or first, depending on the numbering.[/footnote]

of the Society was published, Stow was the sole secretary.

In addition to the necessary committee meetings, the new Society arranged a series of lectures (or ‘Soirees’) over the winter of 1834-5.(20)

[footnote]

- Third Report of the Glasgow Educational Society’s Normal Seminary, 1836, Glasgow 1837, p. 13.

[/footnote]

Rev Dr David Welsh, who became Professor of Church History at Edinburgh University and who had recently visited Prussia, gave the introductory lecture on November 6th, 1834. He claimed that the chief defect in the Scottish Parochial School system was ‘the want of professional training on the part of those who are employed as teachers’. Interestingly, one response to Colquhoun’s ‘Queries’ had argued that all that was required was an increase in teachers’ salaries, unrelated to any training or dependence on children’s fees, as a surety of teacher-effectiveness : ‘I perceive it seems to be a question with you whether or how far salaries to teachers are consistent with a due regard to their efficiency’.(21)

[footnote]Letter to J. C. Colquhoun Esq. M.P. from ‘A Parish Schoolmaster’, Kirknewton, written January 25th, 1834, and appeared in The Glasgow Herald, 10th February 1834. Ironically, a student trained at the college was later to teach in Kirknewton.[/footnote]

Thus then, as indeed now, the equation of salary with training and quality assurance was an issue, and one which Stow later exploited to attract students, since teachers trained at the Glasgow Normal Seminary became a valued commodity. The content of the other lectures, given the events to come, were a portent of more troubled times ahead. The three ministers on the committee, Buchanan, Brown and Lorimer, devoted their lectures to the necessary role of the established church in the provision of parish schools.(22)

[footnote]

- 17 November, Rev. R. Buchanan: ‘On the Superintending Power of the Church of Scotland over the Parochial Schools’; 1 December Rev. Mr Brown of Anderston: ‘Religious Securities necessary to a National System of Education’ ; and 15 December Rev J. Lorimer: ‘Services which the Church of Scotland has rendered to the cause of Education in every period of History’.

[/footnote]

The aims of the Society,(23)

[footnote]Strictly speaking the Society was still an ‘Association’ at this point: the term has been used here for simplicity.[/footnote]

no doubt hammered out over many a wintry night, reflect the enthusiasm for enquiry and debate as well as a business-like approach to involving the Government in response to the Wilberforce Committee statement:

• To obtain and diffuse information regarding the popular schools of our own and other countries – their excellence and defects;

• To awaken our countrymen to the educational wants of Scotland;

• To solicit Parliamentary enquiry and aid on behalf of the extension and improvement of our parochial schools; and

• To establish a Normal Seminary for the training of teachers in the most approved modes of intellectual and moral training so that schoolmasters (sic) may enjoy a complete and professional education’.(24)

[footnote]

- Constitution and Regulations of the Glasgow Educational Society in Hints towards the formation of a Normal Seminary in Glasgow for the professional Training of Schoolmasters, undated but probably, from internal evidence, 1835.

[/footnote]

Of these four aims, it was to the training of teachers that the Society now gave its full attention. Lacking the means for a ‘Normal Seminary’ the first step was to give official recognition to the role of the existing schools, as models for teacher-training. A sub-committee was set up, including Stow, and visits made to all the parochial schools in Glasgow and the suburbs, but it was perhaps inevitable that those associated with the Glasgow Infant School Society were selected:

‘The Committee must have been embarrassed in making a selection of Model Schools, had not their choice been circumscribed by the necessity of fixing on schools as Models in which the young teacher might be instructed not only in the best system of intellectual training, but which, from their superior accommodation, as well as other advantages, would afford scope for the full development of a system of normal training also. With these objects in view, the Committee are decidedly of opinion that St John’s Parochial School, Annfie1d, under the care of Mr Auld, deserves the preference as a Model Juvenile School; combining the greatest number of advantages for the object contemplated by the Society.

The Committee also report that St Andrew’s Parochial Infant School, Saltmarket, already known by the name of ‘The Model Infant School’, and under the charge of Mr Caughie, is justly entitled to be held up to public attention, as exhibiting the best and purest specimen with which they are acquainted, of an Infant school; and as, in all respects, well fitted for receiving young men to be trained as masters. (25)

[footnote]

- Hints (1835) op cit. p. 7, digitised version. Cf. The Glasgow Herald, 15th May 1835. St Andrew’s was the school which originated in The Drygate.

[/footnote]

A week later, on 21st May, 1835, at the ‘Examination of the Educational Society’s Model Infant School’ George Lewis, the Secretary, stated that the adoption of the St Andrew’s Parochial Infant School ‘was the first step towards a Normal Seminary’.(26)

[footnote]The Glasgow Herald, 21st May 1835.[/footnote]

As recognition that these two schools were now model schools of the Normal Seminary, the Glasgow Educational Society agreed to appoint an assistant to Mr Auld in St John’s and to contribute an annual sum of £60 towards its upkeep. Similarly, the Society agreed to share the cost of St Andrews with the Glasgow Infant School Society,(27)

[footnote]

- Hints (1835) op cit, p. 10, digitised version.

[/footnote]

a first acknowledgement that schools required extra staffing if they were to be involved in the training of teachers. With these arrangements in place,(28)

[footnote]The Society was later to recommend the approach of using stand alone ‘Model Schools’ for teacher training either for an experimental initiatory period; or in small towns where there were insufficient numbers to justify the erection of a college.[/footnote]

the embryo ‘Normal Seminary’ was open to receive students.

The Glasgow Normal Seminary

Almost certainly, given the visit to Prussia by both Welsh and McCrie, the first principal-designate, the Society adopted the term ‘normal’ from ‘école normale’ denoting a school for the training of teachers.(29)

[footnote]In 1685, Saint John Baptist de La Salle, founder of the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, established what is generally considered to be the first normal school, the École Normale, in Reims. www.wikipedia.org[/footnote]

In turn, the phrase probably comes from ‘norma’ meaning the establishment of teaching standards or norms.(30)

[footnote]

- The term was used by James Simpson in The Philosophy of Education with its practical application to a system and plan of popular education as a national object, 2nd ed.. Edinburgh: 1836 Quoted Houseman, op cit, 46. The author (almost certainly Stow) of ‘Hints on the formation and conduct of a general model normal school for training teachers to supply the demand of a national system of popular education’ also uses the term. The expression became widespread in the UK. Bangor Normal College (Coleg Normal), for example, was founded in 1858 and was still using the name when it became part of the University of Wales in 1996.

[/footnote]

Clearly the term caused some confusion:

GRANNY:

Weel, ye see, when I cam’ in first into this grand place, I keekit through the glass-door there, and I saw a wheen big chiels, man-muckle, mair nor half a hundred amaist, sitting like in a kirk gallery. Your wee weans hae grown big surely since I saw them last.

MASTER:

These, Mistress, are Normal Students.

GRANNY:

What kind o’ students do ye call them? Norman? Normans! They’re no Frenchmen, are they?

MASTER:

It’s not Norman; Normal is the name. We call this a Normal Seminary. Some call it a schoolmasters’ college.

GRANNY:

An’ what call ye Normal then?

MASTER:

Normal means a rule – or rule of teaching. (31)

[footnote]Stow. (1860) Granny and Leezy, op cit, 6th ed., pps 59, 60, digitised version.[/footnote]

Despite the success of the use of individual model schools to train teachers, their disadvantages were obvious. An ‘Appeal Letter’ of 1836 succinctly enumerates the problems: ‘The distance of these schools from each other – being more than a mile apart, the want of the necessary class-rooms, as miniature school-rooms, for the accommodation of the master pupils attending for the purpose of being trained as teachers, and various other inconveniences’.(32)

[footnote]

- Letter of appeal for the Glasgow Educational Society, 31st December, 1836.

[/footnote]

A small committee was formed, including Stow, which began fund-raising for the formation of an institution. Subscriptions flowed in and by June 1836, £2,260.12.0(33)

[footnote]

- Glasgow Educational Society’s Third Report, 1836 (published 1837).

[/footnote]

had been raised. A second committee, also including Stow, was appointed to select a location and supervise the building works. A site was purchased in Dundas Vale, on the New City Road.(34)

[footnote]

- ‘A small field was fixed upon – value £2540 – and purchased at a moderate price per square yard; of which about one-fifth may be disposed of, should the Seminary not require to be further enlarged. The situation is Dundas Vale, west end of Cowcaddens, in the immediate vicinity of a large manufacturing population.’ GES Third Report (1836), p. 22.

[/footnote]

The College was planned to incorporate seventeen classrooms,(35)

[footnote]

- One each for an Infant Model School, a Juvenile School, a Commercial School, and a Female School of Industry; and thirteen classrooms for the students.

[/footnote]

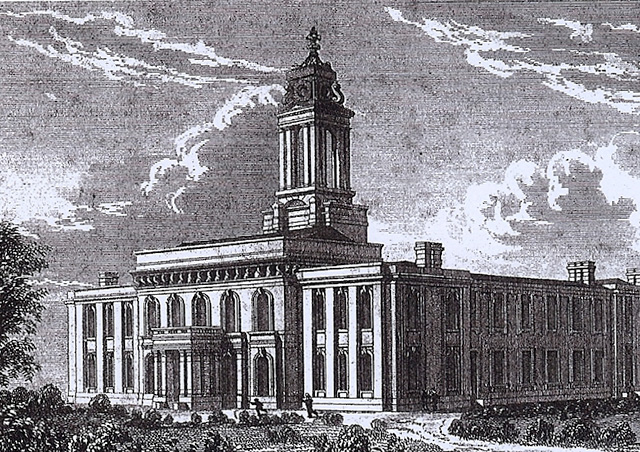

playgrounds, a library, a museum and a Rector’s house and could accommodate a thousand children and a hundred students. The building itself, designed by David Hamilton, architect, and built by William York,(36)

[footnote]

- Pagan, James. (1847). ‘The Glasgow Normal Seminary’ in Sketch of the history of Glasgow: Stuart. p.126-7

[/footnote]

has been worth preserving:

‘The style is simple Italian Renaissance, arched windows being set in recesses formed by plain pilasters. The doorway is in the centre and entered through a classical porch with double square pillars. At the back a tower rises to form a pilastered and pedimented belfry with dock above, the whole capped by an acanthus finial.’(37)

[footnote]

- Wordsall, Frank, (1982). Victorian City. Glasgow: Richard Drew Publishing 1982. No. 36: Dundas Vale Teachers’ Centre, 6 New City Road.

[/footnote]

When the post of principal was first advertised in January 1835,(38)

[footnote]

- For ‘a gentleman of liberal education, of decided Christian character and of about 30 years of age and of mature and cultivated mind’.

[/footnote]

Thomas Carlyle, at least, expressed an interest. Although this little bit of personal history has given rise to speculation, nothing came of it. Either he did not, in the end, apply or the Society considered him unsuitable. Gunn notes that ‘Carlyle had educational ideas which would have done much to widen the outlook of his students’.(39)

[footnote]

- Gunn, John (1921) Maurice Paterson. Nelson, 1921. p. 74.

[/footnote]

Instead, the position was re-advertised, giving the salary as £300 a year for a term of three years.(40)

[footnote]

- ‘42 Gentlemen connected with the West of Scotland, and interested in the improvement of an Educational system, having offered £10 a year for that period, to enable the Society to carry forward their design of instituting a Seminary for Schoolmasters in the Metropolis of the West of Scotland.’ The Glasgow Herald, 11th September, 1835.

[/footnote]

The duties were ‘to supervise the training of teachers in model schools in general knowledge, but especially in the geography, history, prophecies, miracles, doctrines and precepts of Holy Scriptures’.(41)

[footnote]

- The Glasgow Herald, September 11th, 1835.

[/footnote]

Mr John McCrie(42)

[footnote]

- The son of the biographer of Knox and Melville.

[/footnote]

was appointed. He spent the next seven or eight months in Germany and France, visiting educational institutions.

On November 14th, 1836, after a procession of about five hundred prominent citizens, including representatives of various organisations escorted by the police and a military band, the foundation stone was laid by J. C. Colquhoun. Stow gave the address on the aims of the Society.(43)

[footnote]

- Third report of the Glasgow Educational Society, p. 22; The Glasgow Herald, November 18th, 1836; and The Glasgow Courier, November 15th, 1836.

[/footnote]

The Foundation Stone of the Four Model Schools of the Glasgow Educational Society’s Normal Seminary was laid at Dundas Vale, West End of Cowcaddens, on Monday afternoon. The Merchants’ and Trades’ Houses, the Commissioners of Police, the Clergy and Kirk Sessions, and also a considerable number of private gentlemen connected with the Society, met at the Trades’ Hall, where they formed into procession, under the direction of Captain Miller. They then proceeded to the site of the proposed building, preceded by the band of the 14th Light Dragoons, and accompanied by a fine body of Police. The ceremony of laying the Foundation Stone was performed by J. C. Colquhoun, Esq., President of the Educational Society, and the duties of Chaplain by Dr McLeod. Mr Colquhoun and Mr Stow afterwards addressed the gentlemen at some length.

After which excitement, John McCrie returned to give his first lecture to students on January 26th, 1837 and began a course of ‘Theoretical & Practical Training in the Art of Teaching, and the various branches of the profession’. He also took part in a series of public lectures, giving three himself on – ‘The Nature and Ends of Education in general’, ‘The Principles of Education applied to the Infant and Juvenile Schools’ and ‘On the Public School as a preparation for after life’.(44)

[footnote]

- Scottish Guardian, February 14th, 1837.

[/footnote]

On Tuesday, October 31st, 1837 the Glasgow Normal Seminary was formally opened in the, by now, completed building.(45)

[footnote]

- Ian McKellar in Schoolmaisters to be taught? Never! appears to be the only one to spot that the newspaper accounts were published a few days later in November, giving rise to the more commonly-held date of November 1837. A ‘day-of-the-week calculator’ indicates that his dating is correct: the ‘last Tuesday’ referred to in the reports was October 31st.

[/footnote]

This was to be the happiest moment for the next decade so perhaps it may be helpful to pause and take stock. The pace of development had been hectic moving from proposition to foundation stone in three years. Committees, sub-committees and Ladies Committees were well-administered and, judging by the outcomes, effective. Influential and able men were giving their moral and intellectual support by holding office, lecturing at interesting Soirees, and writing in the press, to Parliament, and to stir things up. There must have been a tremendous sense of achievement in the smooth-running of five infant schools, two of them acting as ‘model’ schools for the training of teachers for the extension of schooling in Glasgow and beyond. Many of those involved doubled up as Presidents, Treasurers and Secretaries – and auditors and recruitment officers(46)

[footnote]Stow was one of the auditors of the Annfield School accounts of which that for 1825 survives; and in a letter to Chalmers dated 7th April 1824, he lists all the young men, whom he has visited in turn, who are available for teaching in Sabbath Schools. There is no reason to suppose, from the tenor of his later letters, that this detailed organisation was not continued.[/footnote]

– of the burgeoning Sabbath Schools. Nearly five hundred men and women associated with the GISS and later GES have been identified(47)

[footnote]A list of the 505 men and women involved in the GISS and GES, with details where available is given in a separate post.[/footnote]

and even a cursory glance suggests how active and generous they were. Apart from the well-heeled and eminent – Collins, Colquhoun, Findlay, Ewing, Fleming and the Hamiltons of Sundrum in Ayrshire – there were those such as Donald Cuthbertson who was a Councillor (1828-1834), Magistrate (1828-1833), a Sabbath School Teacher in St John’s (1819), Deacon (1828), Elder (1833) and a member of the committee of St David’s Parish Infant School. And they were generous. Hugh Brown, for example, contributed to the new Chalmers’ Parish Church in Claythorn Street, was a shareholder and subscriber to Chalmers’ Street Infant School and Female Sewing School and subscribed £80 to the ‘Society for erecting additional parochial churches’. Indeed, most of the GES Committee made substantial donations to this Society in the very year (1836) that they were raising money for the Normal Seminary. Often wives donated first and then persuaded their husbands and children to contribute in following years. Many lived in the same area and knew each other socially. Others were in similar occupations – merchants, printers, bankers, writers and rentiers, manufacturers of muslin, calico and carpets and, as we have seen, the church. Of course they were busy, but it was worthwhile, exciting and successful. One of the many illustrative vignettes of this period is of the payment of the Society’s debt of £350 in 1836 (probably for accumulating sundries such as newspaper advertisements and committee teas) by David Bain, the Treasurer and David Stow, the Secretary. When the cause is clearly defined, the committed do not stop to count the cost of involvement.

And then in October, 1837, perhaps indicative of the ominous clouds gathering, John McCrie died of typhus.(48)

[footnote]

- The Scottish Guardian, 5th October, 1837.

[/footnote]

Nevertheless, the announcement of the opening of the College appeared a few days later(49)

[footnote]

- The Scottish Guardian, 2nd November, 1837.

[/footnote]

and, Stow who had already taken on the work of supervision during McCrie’s period abroad, again took charge acting as principal, secretary and lecturer for the next two years. Fortunately, in November 1839, Rev. Robert Cunningham was appointed to the vacant position of rector, a professor of ‘solid scholarship’ with experience in Edinburgh, as Governor of George Watson’s Hospital, and in the United States, where he was principal of Lafayette College. He, like Caughie, hailed from Stranraer and had been the Society’s first choice of Principal before the appointment of McCrie.(50)

[footnote]

- (1868) op cit, p. 152. Robert Cunningham had been the Society’s first choice of principal but he was unavailable at the time.

[/footnote]

It is unfortunate that nearly all accounts of the Glasgow Normal Seminary over the next six years focus on crises – with the finances, the Government, and the Church of Scotland. Before examining these and the impact on the unfolding story, it is worth emphasising that the education of children and the training of teachers progressed steadily. The College was founded on a clearly-expressed rationale and objectives which gave a sense of purpose and direction to policies, decision-making and practice. This sense of cohesion can be attributable, in part, to Stow since his statement on the nature of teacher-training remained consistent in appeals, reports and speeches:

‘A model school, with its complete system of physical, moral, and intellectual training, may show (the teacher) what his own school ought to be, but will not enable him to make it such a school. He must himself be thoroughly instructed in the various branches of knowledge he is afterwards to teach; and must himself learn, by practising it under the immediate direction of a master qualified to train him, the best method of communicating that knowledge to children.’(51)

[footnote]

- Appeal for the Glasgow Educational Society, dated 1836, p. 1, digitised version.

[/footnote]

An analysis of the advertisements, letters, reports and accounts suggests that the Office-Bearers carried on their work competently (although Stow was later to complain that he might as well have been Treasurer in addition to Secretary).(52)

[footnote]Stow wrote ‘You will excuse a Secy. You know I am not invested with the rank of Treasurer’ in a letter to Kay-Shuttleworth dated 30th May, 1841, where he outlines the financial situation of the college.[/footnote]

A Constitution was drawn up. Unfortunately, the third regulation of the Constitution, inserted so innocently in 1834 and repeated annually, stated that: ‘The Society shall consist of persons attached to the principles of a National Religious Establishment, and approving of a connection between the Parochial Schools and the National Church’.(53)

[footnote]

- Constitution and Regulations of the Glasgow Educational Society.

[/footnote]

The irony of this statement would not be lost on the Committee when, in 1843, most of them no longer supported the National Church. The Constitution also ensured that there were sufficient Vice-Presidents to take over when Colquhoun was away on parliamentary business. A quorum of five allowed the routine work of the Committee to go forward when either members failed to turn up, or when it was unnecessary to call them all together. In addition to the usual annual election of office-bearers, six members ‘from the top of the list’ had to stand down each year, although they were eligible for re-election and, indeed, the reports show almost no turn-over of personnel. Arrangements were made for meetings, the creation of sub-committees, and the provision of reports and statements of accounts all of which argues for a business-like approach.

As a result of the non-denominational approach, students from a range of missionary societies were now sent to the College for training including Episcopalian, Wesleyan, United Presbyterian, Independent and Baptist. They came from different countries, including Ireland, fifteen counties in England, the West Indies, Madeira, Bombay and Caffraria (now Transkei and Ciskei) and, of course, the length and breadth of Scotland. Groups of students, otherwise divided by denomination and nationality, were invited to Stow’s home in the evenings for ‘Conversazione’ creating bonds both with him and with each other which were fondly remembered years later. The non-sectarian, multi-racial nature of the College was one of its strengths(54)

[footnote]‘Sectarianism and provincialism were alike lost in enthusiasm for a great educational principle’, Fraser (1868) op cit, p. 156.[/footnote]

– emphasised in the later appeals for funding from the Privy Council. The denominational status of the College staff is unclear, but the children in the model schools represented a wide range of Christian belief and practice – Presbyterian, Episcopalian, Wesleyan, Congregational, Baptist, Socinian, Society of Friends and Roman Catholic.(55)

[footnote]Stow. (1847) National Education, op cit, p. 57, digitised version, p. 33. Italics – my emphasis.[/footnote]

While the Church of England may have preferred Episcopalian teachers, the supply was so limited that Presbyterian students were accepted if ‘they were disposed to conform to the English service – which was generally done’.(56)

[footnote]

- (1847) National Education, op cit, p. 53, digitised version, p. 30.

[/footnote]

Despite the steady flow of students (and their fees), however, the palatial buildings, a lengthy course and the use of specialist lecturers covering a wide curriculum became an increasing financial burden. Writing fifty years later in 1886, David Ross reflected:

‘The expense incurred in the building of the Training College was great, and local contributions came in but slowly; for under the impulse created by Dr. Chalmers each district in the City of Glasgow was too intent on building a church and school for itself, to give material support to an institution designed for the benefit of all. This is just one of the cases where the voluntary method fails. What is everybody’s duty is nobody’s duty; or it is thought to be the duty of the State.’(57)

[footnote]

- Ross, David. Fifty Years of the Training System. 1886. p. 9.

[/footnote]

Notwithstanding its future overwhelming impact on the ownership and development of the College, establishing the exact sum of the debt is problematical. Very few of the references to the accounts, at different dates, correspond. Several problems contribute to a confused picture. Firstly, capital and revenue income and expenditure are merged so that the some of the apparently increasing capital cost must be attributed to the accumulation of maintenance debt while some of the revenue income was used to pay off pressing capital costs.(58)

[footnote]See separate post for further examples.[/footnote]

For example, in 1844 the loyal Wesleyans offered £600 on Stow’s word that the College would remain open long enough for the training of their students to be completed. This should have been put towards salaries and other resources, but was diverted to pay off interest on the capital. The accruing interest on both accounts was sometimes included in the overall outlay, and sometimes not. In the early stages, as long as the interest was met, there appeared to be less pressure to repay loans. Furthermore, there was a tendency to regard loans as a settlement of debts. In an undated letter, Stow wrote to Kay-Shuttleworth ‘All our outstanding debts are paid. We borrowed the sum from the Royal Bank on our personal security’,(59)

[footnote]Stow, letter to Kay-Shuttleworth, undated.[/footnote]

which rather dismisses the loan now due to the bank. Later, a picture emerges of the desperation of using any available income (including personal loans and gifts) to ‘stop us from going down’ as Stow frequently puts it.

Secondly, it is difficult to determine the timing of the money received from the Church of Scotland. James Buchanan in ‘The Ten Years Conflict’,(60)

[footnote]

- Buchanan, James. (1863) The ten years’ conflict: being the history of the Disruption of the Church of Scotland. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Blackie and Son. p. 339.

[/footnote]

a history of the period which led to the Disruption, claims that the General Assembly contributed £2121 in 1834 (a sum suspiciously similar to that given by individuals listed in the Society’s Third Report which might suggest double accounting) and a further £4753 by 1838. Even allowing for the payment of subsistence grants for students (about £288 per year)(61)

[footnote]

- Calculated at 60 students (20 admitted each of three terms) @ 8s per week for a minimum of 12 weeks.

[/footnote]

there appears to be a shortfall in the College’s receipt which, since James Buchanan was joint Treasurer, should have been clarified. Unsurprisingly, the Church of Scotland was equally interested in providing teacher education in Edinburgh and wished to make equal contributions to work in both cities. Since proposals in Edinburgh had not even reached the stage of selecting a suitable site,(62)

[footnote]

- The site in Johnston Terrace close by the Castle was not purchased until 1841 and proved ‘both depressing and inconvenient’, Cruikshank (1970), History of the Training of Teachers in Scotland. University of London Press, p. 53.

[/footnote]

this probably delayed the retrospective payments due to the Glasgow initiative. And, as we have seen, even by 1834 the ‘Auchterarder Case’ had given intimations of the first rumblings of schism within the church so that it is possible that some payments were delayed, and some never made at all.

Thirdly, there were two different government grants available. In 1833, Parliament voted an annual grant of £20,000 to voluntary organisations ‘for the erection of schoolhouses for the education of the poorer classes in Great Britain’ on condition that the organisations raised half the cost themselves.(63)

[footnote]

- This sum increased over the years from 1833-1839 without any Parliamentary control on either the amount or use of the money. Schools and school-houses were built with inappropriate planning, erection and maintenance and were often in ruins a few years later. Neither was there any supervision of the content or quality of teaching. The need for inspection became self-evident.

[/footnote]

In 1835 a further sum of £10,000 was voted by Parliament for the foundation of a national college for the training of teachers.(64)

[footnote]

- And indeed St Mark’s, Chelsea and Borough Road Training College were founded in England as a result.

[/footnote]

Although Stow regarded the College and the model schools as a single institution, he and Welsh were astute (or perhaps naïve) enough to expect some Government aid from the former funds for the College schools and from the latter funds for the College itself. Thus, in December 1834 and May 1835 ‘The Directors of the school, and the Rev. William Black, Minister of the Barony, and Mr D. Stow, Secretary to the Glasgow Infant School Society’ applied for a grant of £150 for the Cowcaddens Infant School which was paid on 29th September 1835, two years before the laying of the college foundation stone.(65)

[footnote]

- School-houses (Scotland). An account of the expenditure of the several sums of £10,000 granted by parliament in the years 1834, 1835, 1836, 1837 and 1838, for the erection of school-houses or model schools in Scotland, p. 399.

[/footnote]

The 1838 Appeal states ‘(The Society) applied to your Lordships for a grant of £1000 being one-half of the estimated expense of two common schools of equal size’ and writing in the fifth edition (1841) Stow states that ‘£1,000 was received three years ago from the Government, as half of the sum required for the erection of one of the two model schools’.(66)

[footnote]

- (1841) The Training System, op cit 5th ed. pps. 94-95.

[/footnote]

Almost certainly, this was for the infant and juvenile schools of the Normal College. It is known, for instance, that the school for the wealthy, which occupied one wing of the Normal Seminary, was closed in order to fulfil the stipulation that school grants were to be expended on the poor. However, it is possible it was for the two Model schools of the society (St John’s Annfield and St Andrew’s, Saltmarket). Nowhere in the accounts is a grant for school provision shown separately from that for the college.

An attempted chronology of Government support might run as follows. In a letter to the Treasury written by GES in 1838, reference is made to a visit paid ‘two years ago’ which would be in 1836 (presumably when the foundation stone was laid):

‘A deputation from the Society waited upon the Right Honourable the Chancellor of the Exchequer(67)

[footnote]

- Thomas Spring Rice (1790–1866), Baron Monteagle.

[/footnote]

about two years ago to ascertain whether he would recommend a grant of £3000 for this purpose, provided a similar sum were raised by voluntary contribution; the proposal was well received by him, but as he was not prepared to give a decided answer, no further steps were then taken, and no formal application was then made to your Lordships.’(68)

[footnote]

- Appeal letter to the Treasury dated 1838.

[/footnote]

Two years after this visit, in March 1838 – the date of the letter – an ‘Appeal to The Right Honourable the Lords Commissioners of Her Majesty’s Treasury’ was formally made for a capital grant of £5,000. This Appeal was signed by two of the Vice-Presidents, the Secretary and the two Treasurers. The Treasury granted £1,000 of this request on 30th May 1838. Whether this was for the schools or the college or the society is unclear.

However, by 1839, the pressure on the Treasury was so great, and indeed the debate over religious or state provision (rather than state support) so acrimonious, that the Government devolved decision-making to the newly-formed Privy Council. A letter from Stow dated 11th October 1839 suggests that a second grant of £1000 was made, this time by the Committee of Council on Education, on condition that the college be subject to government inspection which was willingly accepted.(69)

[footnote]

- Letter from Stow to Right Honourable the Lords of the Committee of Council on Education. October 11th, 1839.

[/footnote]

Nevertheless, the Society was still £3,000 short of its original appeal.

A year elapsed before Stow used his personal influence with Kay-Shuttleworth: ‘Our Society have made haste to pray Her Majestys Most Honble (sic) Committee on Education for a grant of five thousand pounds’.(70)

[footnote]

- Letter of Stow to Kay-Shuttleworth dated 24th January, 1840.

[/footnote]

This led to a third vote of £2,500 making a total grant of £4,500. This is confirmed by the Treasurer’s ‘Report to the British Association Meeting’ held at Glasgow in 1840: ‘The Normal Seminary has cost £15,000, of which His Majesty’s Government granted £4500; £3500 has been obtained by private subscription, and the remaining £7000 stands as a debt on the property. A year later Stow, with a hint of humorous desperation is asking for more:

‘I therefore like a Bankrupt in ordinary business lay before you our forlorn condition as to brass as the Yorkshire man would say & ask your private advice what, course we ought to pursue. May I ask would you advise our applying for as much as finish the buildings in addition to the £2500 so handsomely granted already? Dare we apply for the £700 of interest? Dare we apply for a further grant to liquidate the Debt?’.(71)

[footnote]

- Letter of Stow to Kay-Shuttleworth dated 24th January, 1840.

[/footnote]

There is no record of any further contributions from the Government.

If the Treasury grant was indeed paid (and not just granted) on 30th, May 1838, and if indeed it was for the college and not the schools, then Rusk is right to highlight its significance as being the first Government subsidy for teacher training.(72)

[footnote]Rusk, Robert (1928), op cit, p. 87. He quotes Craik, H. (1914) The state and education, p. 26 and Bartley, G.C.T. (1871) The schools for the people, p. 430, both of whom contradict Rusk’s claim. There is a further complication that the grant was for Model schools but used for teacher training.[/footnote]

However, in the 1838 Appeal letter there is at least a hint that although the sum was granted the Committee did not apply for the money at the time:

This request was lately complied with by your Lordship, as intimated to the Rev. Dr Black and the Rev. Peter Napier,(73)

[footnote]Revs Black and Napier were the commending ministers.[/footnote]

on certain conditions with which the Society are ready to comply, but delay applying for the money until they have laid upon your Lordships all their wants. (My emphasis.)(74)

[footnote]

- Appeal letter to the Treasury dated 1838.

[/footnote]

The ‘Minutes of the Committee of Council on Education for 1854-5’ state that ‘in 1840 a Treasury grant of £1000 and a Privy Council grant of £1000 were made’.(75)

[footnote]

- Minutes of the Committee of Council on Education for 1854-5 Quoted Rusk (1928) op cit p. 87.

[/footnote]

Not only had the Treasury devolved this expenditure to the Privy Council by 1840, but the year is incorrectly given for both grants and, in any case, it would be unlikely that both the Treasury and the Privy Council would make grants in the same year. The Parliamentary Paper 282, dated 3rd June 1839, does certainly suggest that the Treasury made a grant of £1000 on 30th May 1838 in response to an original application on 14th October 1836 (not recorded elsewhere) rather than the Appeal letter of March 1838. Nevertheless, various documents refer to a total Government grant of £4,500 which supports the assumption of two grants of £1,000 plus one of £2,500.

A further complication arises in the calculation of the final costs and debts which are put variously at £12000,(76)

[footnote]

- (1847) National Education, op cit.

[/footnote]

£15,000 (as above), £15,700(77)

[footnote]Correspondence from Kay-Shuttleworth to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland dated February 2nd 1848: ‘The cost of the site and buildings of the Glasgow Normal School was £15,700, of which the Committee of Council granted nearly two-thirds or £9,500’.[/footnote]

and £17,000(78)

[footnote]

- Report on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Normal Schools by John Gordon, Esq., Her Majesty’s Inspector of Schools in Scotland, MCCE Minutes, 1846, Vol. II, p. 488. Gordon was the Scottish HMI from 1844-50 and from 1854-73. Bone, Thomas. (1966) School inspection in Scotland 1840-1966. London: University of London Press. p. 260.

[/footnote]

although the following summary suggests considerably more:

Year To Amount

1836 Purchase of a field £2540

1837 Purchase of ground £2558

Tradesmen’s accounts £3271

Sundry expenses £78

1838 Tradesmen’s accounts £4132

Furniture £127

Interest on debt £308

Sundry expenses £341

1839 Tradesmen’s accounts £470

Furniture £42

Interest on debt £257

Sundry expenses £312

1841 Interest on debt £750

Tradesmen’s accounts £500

Additional work on the new building £3,000

Total £18,686.00 (79)

[footnote]All figures rounded: full details are given in a separate post.[/footnote]

Total capital income amounted to:

Year To Amount

1836 Subscriptions £2260

1837 Subscriptions £2255

1838 Subscriptions £225

Proceeds of Hope Street Property,

of which a gift was made by the Ladies Society £1034

Grant from the Treasury £1000

1839 Subscriptions £60

Grant from the Committee of Council on Education £1000

1840 Grant from the Committee of Council on Education £2,500

Total £10,334.00 (80)

[footnote]Ibid.[/footnote]

Despite the difficulty of reconciling the above synopsis with any summaries quoted by Stow, or indeed the Society, it seems probable that in 1840 the capital debt amounted to about £8,000. The cost was more than financial. Robert Cunningham, the Principal, understandably concerned about the college’s financial instability, left after only a year in post to found the Blair Lodge Academy in Polmont. Stow again became acting Principal, lecturer, secretary and to some extent treasurer. Inevitably for a man with a day-job, he found the work increasingly onerous. In a letter to Kay-Shuttleworth, dated 1841, he wrote: ‘I have just finished thirteen letters this evening … and this is my daily evening work’.(81)

[footnote]Letter from Stow to Kay-Shuttleworth, 30th March, 1841 now in the Shuttleworth Manuscripts, John Rylands Library, University of Manchester.[/footnote]

He had already turned down(82)

[footnote]

- In 1838: Fraser. (1868), op cit, pps. 150, 151.

[/footnote]

an invitation from Kay-Shuttleworth to become one of the first inspectors for Scotland partly on the grounds that that his health was suffering through overwork.(83)

[footnote]

- ‘I would not like to be paid for services in any shape, although I consider it right and proper that all special service should be paid. I have pursued a course of over-exertion for many years, and my medical adviser has told me that if I do not pull in I must be stretched out’ Quoted Chambers (1870) Biographical Dictionary New Edition. Edinburgh: Blackie and Son, p. 407.

[/footnote]

‘I have pursued a course of over-exertion for many years’, he stated drily, ‘and my medical adviser has told me that if I do not pull in I must be stretched out’.

With mounting debts, the Society had no option but to turn once more to the Privy Council. In the meantime, however, the Council had been in discussion with the Church of Scotland over the nature of the inspections which were to take place as a result of the acceptance of Government financial support. While the Government accepted that appointed Inspectors could not interfere with the teaching of religion or with the discipline and management of the schools, reserving inspection for secular subjects only, the Church was anxious to ensure that this restriction was adhered to. Almost as an aside to the main discussion, Kay-Shuttleworth arrived at a happy solution to the financial problems of the Glasgow Educational Society – that, in return for further financial support, the responsibility for, and jurisdiction over, the college should be passed to the Church of Scotland.

Thus the Committee of Council on Education set out in a Minute dated December 21st 1841 that, even accepting the critical report from HM Inspector Mr Gibson,(84)

[footnote]

- John Gibson, an experienced teacher first in the Circus Place School in Edinburgh and then in Madras Academy, St Andrews, was the first Inspector in Scotland. Appointed in 1840, he was initially acceptable to the Church of Scotland. However, in 1843 he seceded during the Disruption and was directed to refrain from the inspection of any schools which were under the superintendence of the Church of Scotland. He had to relinquish his post in 1845 and during the next three years used his experience to organise schools for the Free Church. In 1848 he returned to the Inspectorate to inspect Free Church Schools in receipt of government grants. Meanwhile, John Gordon, who was acceptable to the Church of Scotland, took his place. The first inspectors were paid £450 per annum plus travelling expenses and a maintenance allowance of 15s per day when actually working. This was 50% above the salary of the Principal of the Normal College who received £300 per annum.

[/footnote]

and noting the correspondence from the Glasgow Educational Society and the Education Committee of the Church of Scotland, it was resolved to give £5,000 to the Church of Scotland as a contribution to the cost of the building and £500 per annum as a contribution to maintenance. The conditions included the transfer of the site and buildings to the Church of Scotland ‘in trust for ever, as Model Elementary Schools (for the children of the poor of the city of Glasgow), and as a Normal School (for the instruction and training of schoolmasters of elementary schools, for the children of the labouring classes), to be maintained and conducted by the General Assembly’. The Church of Scotland became responsible for the remaining portion of the debt, quoted by HMI Mr Gibson as £5,677 which must have included mounting revenue costs. An annual maintenance award of £500 was also granted on three conditions, that:

• The children’s weekly subscriptions and the students’ annual fees should also be used to defray the expenses;

• The General Assembly of the Church of Scotland provide an equal amount to the award; and that

• If the Normal College was not suitably maintained by the Church of Scotland, the grant would be withheld.

Following the Disruption, the second and third conditions returned to haunt the Church of Scotland.

Events ground on slowly. On 11th February 1841, the General Assembly’s Education Committee expressed their gratification at these proposals. A deputation from the Glasgow Educational Society, headed by Stow, met with the Education Committee on November 25th, 1842 when the above resolutions were accepted by both parties with the provision that certain members of the Educational Society ‘be personally responsible for the remaining debt of £5,677, on the understanding that the Church of Scotland give such subscriptions and collections, as from time to time may be made, to liquidate that debt’.(85)

[footnote]

- Minutes of the Education Committee of the Church of Scotland, November 25th, 1842. The ‘members’ were Messrs Henry Dunlop, William Brown, John Leadbetter, William Campbell, Hugh Cogan, James Wright, David Stow and James Buchanan. Fraser (1868), op cit, p. 165-6.

[/footnote]

Fraser argues that ‘Mr Stow, though an ardent supporter of the Established Church, did not see the necessity for such a transference, but hoping that it might advance the cause that he had so much at heart, he yielded’.(86)

[footnote]

- Fraser (1868), op cit. p. 163.

[/footnote]

Stow’s obvious relief at the financial outcome of the arrangement was to be short-lived. With a sense of foreboding, Stow appears to have become increasingly concerned about the hand-over to the Church of Scotland. ‘You know’ he writes in a letter to Kay-Shuttleworth on September 21st 1843, ‘that certain gentlemen members of the Glasgow Society agreed to hand over to the General Assembly’s Committee our Institution upon receiving the grant of £5000 from the Committee of Council’ rather suggesting that he was not one of them. When the Government continued to refuse to hand over the £5,000 on the premise that it would ‘aid dissent’, Kay-Shuttleworth came to share Stow’s reservations. He wrote to the Home Secretary, Sir James Graham, acknowledging that it was ‘at my suggestion that the Committee of Council proposed to Mr. Stow and to the Education Committee of the General Assembly that, on condition that £5000 were contributed by the Government towards the liquidation of the debt, the schools should be conveyed to the General Assembly’ but that ‘The great and grievous disruption of the Scotch Church has baffled all calculations, and overthrown all these prudent arrangements’.(87)

[footnote]

- Letter from Kay-Shuttleworth to Sir James Graham quoted Smith, (1923) The life and work of Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth, pps. 199-200.

[/footnote]

Indeed it had, for in May 1843, the Disruption of the Church of Scotland took place with its attendant stymied action and acrimony.

The ‘Report of the Committee of the General Assembly for increasing the Means of Education submitted in May, 1844’ stated that ‘in regard to the Glasgow Normal Seminary the conveyance remains still uncompleted’. Later in 1844, the Committee of Management of the Glasgow Church of Scotland Normal Institution made a regulation that none should be permitted to conduct the training of students who were not members of the Establishment.(88)

[footnote]

- Rusk, Robert. (1958), ‘Origins of the Teacher Training System’ in The Scottish Educational Journal. 2nd May, 1958.

[/footnote]

In effect this would mean the dismissal of all the Free Church staff. It was not until 1845 that the Education Committee could report to the Assembly that ‘the Committee having concluded the arrangement with Government for the transference of this school, the Glasgow School Directors requested to be permitted to retain possession of the building until the 15th May, 1845, which was agreed to’. The protracted debate about the possession of the college and the position of the staff, students and pupils affected not only the Principalship. In a series of letters to Kay-Shuttleworth, Stow complains that:

‘This delay will inevitably starve out our teachers & compel them to accept one or other of the many offers now in their hands……. Mr. Hislop before the 31st inst. must give an answer to the Directors of a Grammar School whether he will accept the Rectorship of it at a handsome salary & having kept the offer in abeyance fully two years at my request the answer cannot be longer delayed……. . I have lately advanced above £100 to keep the Masters for a little…….., I am certain we have lost half a dozen well educated Men anyone of whom would have suited first & all situations. We have been under the necessity of declining such men weekly. I wish we were not quite so poor.’ (89)

[footnote]

- Letters to Kay-Shuttleworth dated 16th and 26th December 1843.

[/footnote]

The Normal Seminary was eventually opened in the name of the General Assembly’s Committee on the 16th of May, 1845. A local Committee for managing the Glasgow Normal Seminary was formed, and the Minutes of this Committee state ‘The local Committee for managing the Glasgow Normal School have to report that the buildings, etc., came under their charge at Whitsunday last’. At this point, as forewarned by John McCrae, secretary of the Education Committee of the Church of Scotland, the stipulation came into force ‘that all teachers of schools under the management of the Church of Scotland must be in communion and in connection with that Church’.(90)

[footnote]

- Letter from John McCrae, secretary of the Education Committee of the Church of Scotland, quoted Fraser, op cit, p. 172.

[/footnote]

That Stow was angry about the turn of events is surprising only given his otherwise equanimity of character. Fraser succinctly sums up his situation:

‘He refused to believe that because he was now a member of the Free Church, and for no other reason, he was unfit for any further share in the management of an institution which his own exertions had been chiefly instrumental in originating and establishing. He pled, that, hitherto, teachers had been appointed by him, irrespective of church connections, if but qualified by attainment and character, that the institution was really in all respects national, being attended by pupils and students connected with the Established Church of Scotland, the Church of England, the Wesleyan, Independent, Baptist, and other dissenting bodies – that it was hard that he and his coadjutors should be held personally responsible for a debt of £5,677 on an institution from which they were henceforth to be excluded that really, as directors, they had adopted no new views – that they held every doctrine as before – that they still vindicated the principle of an Established Church – that they had never moved from their position – and that the only changes were unexpected interpretations of ecclesiastical law.’(91)

[footnote]

- (1868) op, p. 167.

[/footnote]

Stow’s letter to Kay-Shuttleworth, dated 21st September 1843, aptly reflects the Glasgow – Edinburgh distrust:

I had no hope, as I took the liberty of stating to Sir James Graham, that we would receive fair play, for allow me to say that although the Glasgow folks have no jealousy of Edinb yet the Edinb folks, one & all ministers & people, seem to look with an exceedingly jealous eye on every thing that comes or may come from the west. We are now no better off in this respect with the present established Church Comt. which is in reality an Edinb Comt.

Stow was particularly irate that the Church of Scotland should inherit the college buildings and land:

‘Relying on the General Assembly’s Comt. to raise in conjunction with ourselves the remaining debt of £6000 after receiving the proposed grant of £5000 we freely offered to hand over the whole Buildings & ground worth greatly more than £5000 (the ground alone is worth that sum) to the Assembly’s Comt. agreeable to the wishes of the Committee of Council.’

And he was embittered that the college’s welcome to men and women of all denominations should now be so spectacularly reversed when his own position was in peril:

‘We have no rule against a Master or Director being of the Secession as a proof of which Caughie who has now been 17 years with us was one & McCrie our first Rector another. Both however held Church principles & we have two Episcopalians in our direction. A new law therefore must be made by the Church to put us all out, myself among the number.’

There was to be no retreat. A sad little advertisement appeared in The Scottish Guardian in August 1844 stating that ‘a few students may be admitted into the Institution for the winter session, not later than 1st September next’.(92)

[footnote]The Scottish Guardian, 2nd August 1844.[/footnote]

This was followed by advance warning of the dismissal of staff:

‘The Subscriber begs to inform Clergymen, and Directors of Schools that after May next, The Buildings and Training-Grounds of this Seminary will fall into the hands of the Committee of the Established Church, and that that Committee have made a new law for the Institution, by which none shall be permitted to conduct the training of pupils or students who are not members of the Establishment. This involves the dismissal of all the present experienced Masters who adhere to the Free Church. And as few who are now members of the Established Church have been trained, and none of these of sufficient practical experience to conduct the Institution, I regret exceedingly that after the present session it will not be in our power from Scotland to supply the greatly increasing demand for Trainers.’(93)

[footnote]

- The Scottish Guardian, 13th September 1844.

[/footnote]

The Free Church Training College

Since Stow had anticipated this situation as early as 1843, plans were well in hand for the establishment of a rival Free Church Seminary. A site was purchased in 1844, further up the hill from Cowcaddens. Stow laid the Foundation Stone on 18th July 1845 along with:

‘A Protest by the Ministers and Elders of the Free Church against the Disruption, a list of subscribers to the building fund, various numbers of The Scottish Guardian, including one of the day of issue, the ‘last edition(94)

[footnote]

- This would probably be the 6th ed., 1845. The last was the 11th, 1859.

[/footnote]

of Stow’s Training System, and several coins of the period. The architect of the new college was Mr. Thomas Burns, and the builder Mr. John Christie.’(95)

[footnote]Houseman, op cit, p. 68. Markus (1982) suggests that the architect was Charles Wilson but queries this, p. 253.[/footnote]

The new buildings were formally opened on 12th August 1845 at a cost of £6,390 although almost inevitably Rusk notes that ‘The figures in regard to ground and buildings do not quite agree with an Abstract Statement of the Income and Expenditure for the three years ending 31 March, 1848, prefixed to the Treasurer’s Letter Book’.(96)

[footnote]

- Minutes of the Free Church Assembly pps. 64-5 quoted Rusk. (1928) op cit, p. 121.

[/footnote]

Despite the titanic necessity for funds to re-house evicted manse families, to build new churches and schools, to guarantee salaries of £25 p.a. for the teachers, and to send £65,000 for the relief of famine in the Highlands,(97)

[footnote]

- Oliver, Neil. (2009) ‘A history of Scotland’. The Open University in conjunction with BBC Scotland.

[/footnote]

the Free Church Assembly felt bound to apportion £2,000 to the costs. With legacies amounting to £2,000, subscriptions of £2,648 and a grant from the Committee of Council of £3,000, the total debt was cleared in four years. The Proceedings of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland for 1846 proudly records that:

‘In Glasgow, on the 7th May last year, (sic: 8th May) we marched 700 children, all the teachers and all the students, out of the buildings which were then to fall into the hands of the Establishment. We assembled in a wooden erection built on what was destined to be the future play-ground of our Normal School. On that day the walls of the new seminary were but scarcely appearing, but by the 12th of August, three months and five days thereafter, the multitude of children, with the whole of the teachers and the students connected with them, assembled in the new premises.’(98)

[footnote]

- The Proceedings of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland for 1846, pp. 182-3.

[/footnote]

All the staff except the music teacher,(99)

[footnote]

- (1857) The State of our Educational Enterprises: A Report of an Examination into the Working, Results and Tendencies of the chief Public Educational Experiments in Great Britain and Ireland. Glasgow, Blackie and Son, 1857, p. 99

[/footnote]

and all but one of the Trustees, but including Robert Hislop, the Master of the Senior School with oversight of the college as a whole, and David Caughie the Master of the Juvenile Schools, transferred to the new Institution leaving the Glasgow Normal College in disarray. Stow might have felt some justice in the refusal of the Committee of Council on Education to sanction the payment of £500 to the Church of Scotland for the past year ‘Both on account of the absence of an appointment of a Rector in the Normal School of Glasgow, and the non-fulfilment of the condition as to expenditure in that school, as well as in consideration of the fact that the improvements necessary for the prosperity of these institutions have only been resolved upon at a very recent period’.(100)

[footnote]Letter, dated 18 June 1847, from J. P. Kay-Shuttleworth, Esq., acting on behalf of the Committee of Council on Education, to the Church of Scotland Education Committee.[/footnote]

Wood(101)

[footnote]

- Wood, Sir Henry (1987) op cit, p. 47. No ‘subscriptions or collections’ were ever raised to liquidate the debt of £5,677 born by the ‘certain members’ and the assumption must be that the ‘certain members’ paid it.

[/footnote]

argues that ‘Stow and his friends resiled from their agreement to pay the excess over the £5,000 grant from the Committee of Council’ leaving the college still burdened with debt. However, in 1846 the Committee on Education of the Privy Council refused to pay the annual grant of £1,000 to the Church of Scotland partly on the grounds that the Education Committee had not expended a similar sum. Their response was to cobble together the monies which had indeed been spent (£1683, 15s. 3d. from April 1845 to May 1847 which was less than £1000 per year) adding the gratuitous work and resources of the secretary and treasurer.(102)

[footnote]

- ‘With regard to the second charge — the non-fulfilment of the condition as to expenditure — the committee have to remark, that since May 1845 up to May 1847, the expenditure has been £1683, 15s. 3d. They have been naturally desirous to avoid all extravagance, and have looked more to the efficiency of the seminary down to the necessity of keeping up an expenditure that was not required. They beg, however, to remark, that is unless a considerable amount of gratuitous service had been rendered, the expense would have been greatly increased.’ Church of Scotland reply to ‘Reply by the Education Committee to Mr K. Shuttleworth’s letter’, dated 18th of January 1848.

[/footnote]

If they could show that The Church of Scotland (rather than Stow and his friends) had paid the debt of £5,667 the grant would surely have been paid.

Not that the Free Church College was without its problems. The children who marched so jubilantly up the hill to the tents on 8th May had to spend the next few months in ‘long canvas-covered tents erected on what was to be their playground, with a saw-dust floor, and with rough benches’.(103)

[footnote]

- (1868) op cit, p. 177.

[/footnote]

Unhappily, some teaching staff may also have lost their homes. The plans of the Normal College illustrated accommodation for the Infant and Juvenile Masters’ houses and in the Scottish Census of 1841, Robert Hislop, for example, is recorded as a teacher living in St George’s in the Fields Parish, with an address at the Normal Seminary New City Road, Glasgow. By the Census of 1851, he had become ‘Rector of a Normal Seminary’ and was living at 11, Buccleuch Street.

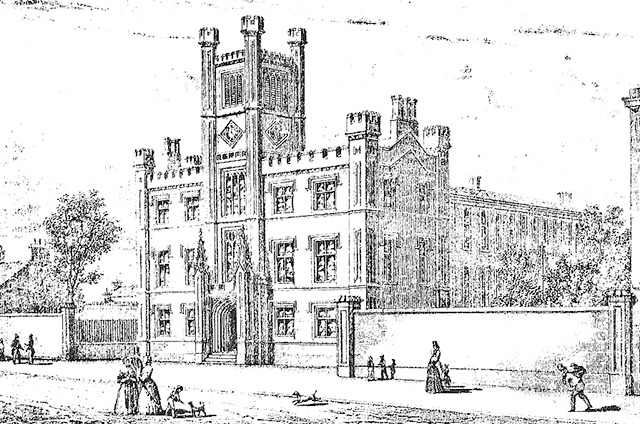

Nevertheless, the new buildings were worth waiting for: ‘The style of the new building is Gothic’, wrote Fraser, ‘the front giving an example of decorated English, with mullions in the centre, and crocketed turrets. The general effect is light and pleasing. The internal accommodation is ample, embracing ten class-rooms, four large halls, students’ rooms, library and museum, and janitor’s house; while, outside, there are spacious play-grounds’.(104)

[footnote]Fraser. (1868) op cit, p. 183.[/footnote]

Perhaps it is a tribute to the detailed specification of the modus operandi and rigorous efficiency of the old Normal College, that the new institution was up and running so quickly. The organization was effective, including four graded schools which allowed the grouping of pupils of similar age, so that the sympathy of numbers might be greater, and teaching more direct. ‘The work’, Fraser once more recalls, ‘was carried forward with enthusiasm. Each school was crowded. Students of different denominations filled the halls, and Mr Stow found a fresh field here, which he at once began to cultivate with unfaltering hopefulness’.(105)

[footnote]

- (1868) op cit, p. 184.

[/footnote]

And on a private visit to Stow, Kay-Shuttleworth was able to uplift his spirits by reporting, presumably on the back of Gibson’s inspections, that his schools ‘were in a more successful condition than before the secession’.(106)

[footnote]

- Quoted Smith (1923), p. 201 footnote 1. Stow must have been unhappy, however, at the grants to Kneller College which by 1851 totalled £41,809. Mason (1985), p. 29. The principal of Kneller College, Frederick Temple, was Stow’s fourth cousin. The college closed in 1856.

[/footnote]

Despite the good fortunes of the Free Church College Stow always felt a longing for the Glasgow Normal Seminary. Dr David Ross, Rector of Dundas Vale Training College (the Old Glasgow Normal College ) in 1893, remembered Stow personally:

‘To me David Stow was known thirty years ago as an occasional wanderer in the New City Road, flitting silently by the scene of his early labours in Dundas Vale. From time to time an eager glance and a nervous tremor betrayed that an estrangement of seventeen years had not lessened his regard for his first and beloved child. Those who knew him spoke of a respect amounting to reverence, and I used to feel a kind of awe come over me as I passed that silent, self-restrained figure.’(107)

[footnote]

Thomson, op cit, p.21.

[/footnote]